Highlights

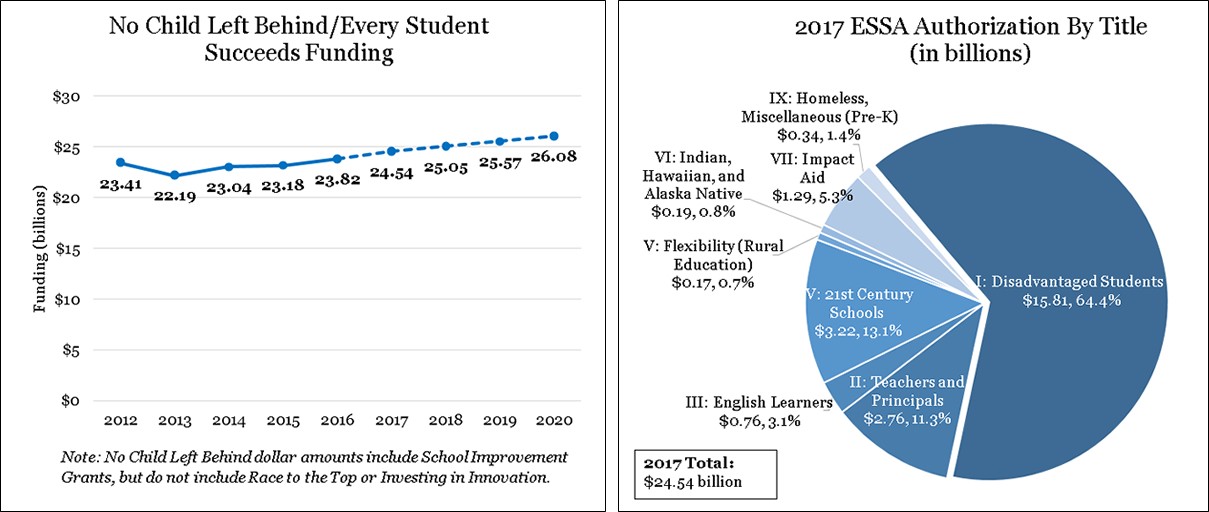

Similar funding levels. Every Student Succeeds authorizes similar funding levels as No Child Left Behind. Funding is authorized for four years, and increases steadily from $24.54 billion in fiscal year 2017 to $26.08 billion in fiscal year 2020.

School Improvement Grants eliminated. Every Student Succeeds terminates the School Improvement Grant program, which provided additional money for schools identified for intervention. The new law requires states to reserve a greater part of their Title I budget (7 percent, increased from 4 percent) specifically for school turnaround and improvement, however.

Multiple programs consolidated into $1.6 billion block grant. Every Student Succeeds combines funding for many programs – such as school counseling, smaller learning communities, gifted and talented students, physical education, and the arts – into a single block grant. While No Child Left Behind created separate programs for these initiatives, some had not been individually funded for several years. Although school districts have increased flexibility to use grant funds where needed, Every Student Succeeds imposes some minimum funding requirements.

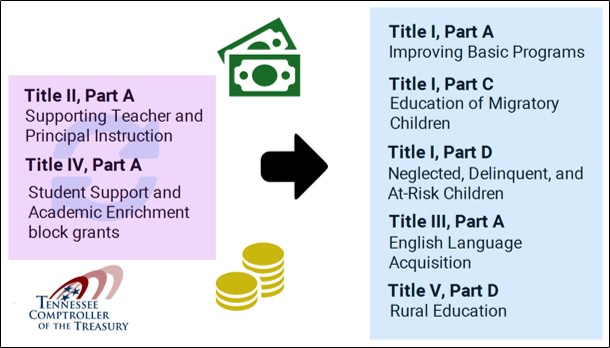

Increased federal funding flexibility. States and school districts may now transfer any or all of their federal funding between Title II, Part A (Supporting Teacher and Principal Instruction) and Title IV, Part A (Student Support and Academic Enrichment block grants). Additionally, states and districts may also transfer funds originally intended for Title II-A or Title IV-A to several other titles.

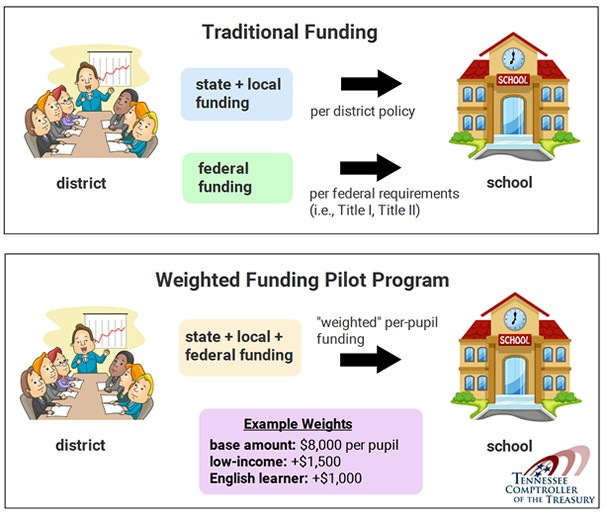

Weighted funding pilot program. Fifty school districts nationwide may include federal funds in a weighted funding system that directs more money to schools with higher numbers of disadvantaged students. Federal funds from several areas of Every Student Succeeds, including Title I, Title II, and Title III, may be allotted toward the weighted funding system.

Pay for success funding. Funding from Title I, Part D and Title IV, Part A may be used in pay for success programs. Pay for success programs allow private investors to contribute money to public projects – however, the investors are only repaid if the projects are successful.

Authorizations

Overall funding levels for Every Student Succeeds (ESSA) are similar to No Child Left Behind (NCLB). For fiscal year 2016, the last year NCLB funding formulas are is in effect, $23.82 billion was allotted. In fiscal year 2017, the first year ESSA’s funding formulas take effect, $24.54 billion has been authorized, an increase of about 3 percent. ESSA funds have been authorized through 2020 and steadily increase through the years, topping out at $26.08 billion.

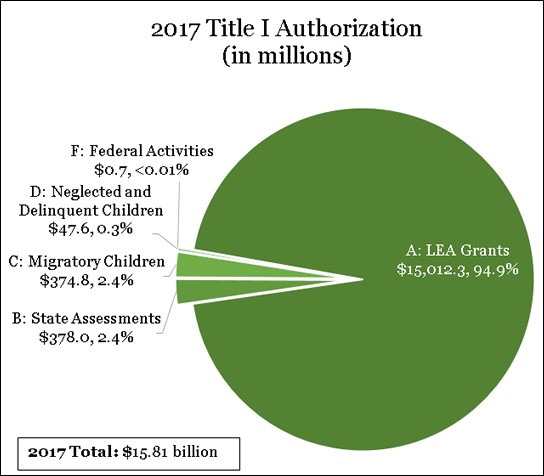

The majority of ESSA funding – nearly 65 percent, or $15.81 billion authorized in federal fiscal year 2016-17 for use in school year 2017-18 – goes toward Title I. Title II and Title IV, focusing on teachers and principals and 21st Century Schools, respectively, together account for another 25 percent of the budget.

Title I – Disadvantaged Students

Title I is the largest part of the Every Student Succeeds budget. About $15 billion, or nearly 95 percent, of Title I money goes toward state and school district grants under Part A. 1 These funds are intended to help low-income students reach proficiency; on its own, “Title I funding” typically refers to funds under Title I, Part A. Part A’s stated purpose is to “provide all children significant opportunity to receive a fair, equitable, and high-quality education, and to close educational achievement gaps.” 2

School districts use Part A subgrants to improve their schools’ programs and instruction. A school where at least 40 percent of enrolled students are economically disadvantaged may operate a schoolwide program – that is, the school may use Title I, Part A funds to improve its entire program. 3 A school whose low-income population is less than 40 percent of total enrollment operates a targeted assistance program. Targeted assistance programs focus Title I, Part A funding on students who are failing or at risk of failing. 4

In school year 2015-16, 1,234 of Tennessee’s approximately 1,800 schools received Title I, Part A funding. The vast majority – 1,211 schools, or 98 percent – operate schoolwide assistance programs. 5

Under ESSA, states have the power to waive the 40 percent requirement: upon receiving a waiver, schools with lower concentrations of low-income students may still operate schoolwide programs. 6

In February 2016, the U.S. Department of Education released preliminary estimates of federal funding for fiscal year 2016-17. Tennessee is projected to receive just over $308 million in Title I, Part A funds, a 2 percent increase from fiscal year 2015-16.

Tennessee is expected to receive almost $2 million for Title I, Part C (Migratory Children) in fiscal year 2016-17, or nearly two and a half times more funding than the previous fiscal year. Finally, the state’s funding for Title I, Part D (Neglected and Delinquent Children) will remain constant at roughly $357,000. 7

School Improvement Grants

Every Student Succeeds eliminates School Improvement Grants (SIG). 8 Under No Child Left Behind, the SIG program provided additional federal grant money to states – states then made subgrants to districts specifically for schools identified for intervention. 9 To receive SIG money, however, schools had to put in place one of four SIG turnaround models: transformation, turnaround, restart, or closure. 10

In 2014, SIG grants totaled nearly $506 million nationwide, and Tennessee received almost $9.2 million. 11, 12 For school year 2015-16, Tennessee allotted nearly $2 million in SIG funds to the Achievement School District, just over $500,000 to Knox County Schools, over $3 million to Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools, and almost $5 million to Shelby County Schools. 13 Over the course of three years, SIG grants for these four districts will total nearly $32 million. 14

In addition to SIG grants, states were required to reserve 4 percent of their Title I, Part A funds specifically for school intervention under NCLB. Those funds were given directly to districts for schools identified for improvement, corrective action, or restructuring. 15 Under the waiver, Tennessee gave this state reservation to priority and focus schools. 16

ESSA increases this state reservation from 4 to 7 percent of Title I, Part A funding. 17 In fiscal year 2015-16, Tennessee received $283.7 million in Title I, Part A funds. 18 Four percent of this just over $11.3 million; 7 percent is $19.9 million. ESSA’s 3 percent increase adds nearly $8.5 million reserved at the state level for school improvement. This difference nearly equals the funds Tennessee previously received in SIG grants.

State Assessment Grants

Under Title I, Part B, states may apply for state assessment grants to develop statewide tests and standards. If states already have these standards and tests in place, they may use the grant money for other related activities – providing accommodations for English learners, improving tests for students with disabilities, or developing assessments in other subjects, for example.

States and school districts may also use grant funds to audit their assessment systems. 19

Title II – Teachers and Principals

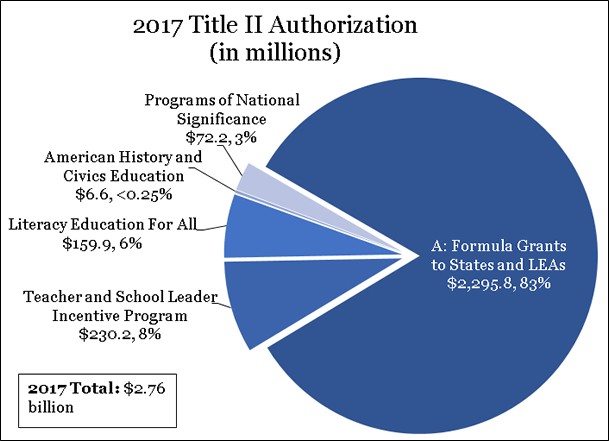

Title II intends to improve teacher and principal quality. Nearly $2.3 billion, or the majority of Title II funds, are given to states through formula grants under Part A. 20 States then distribute this money to school districts through subgrants. 21 Some examples of district activities under Title II, Part A include:

- improving teacher and principal evaluation systems;

- implementing programs to recruit, hire, and retain effective teachers;

- recruiting individuals from other areas – such as career professionals, veterans, and recent college graduates – to become teachers and principals;

- reducing class size;

- providing professional development for teachers, principals, and other school staff; and

- providing training to support special groups of students, such as English learners, students with disabilities, and gifted and talented children. 22

Every Student Succeeds alters the federal funding formula for these grants. Currently, all states receive a base amount, calculated from the amounts received in fiscal year 2001 before the passage of No Child Left Behind. Any additional funds are allotted by formula. Thirty-five percent of a state’s excess share is based on its population of school-age children compared to other states. The other 65 percent depends on the number of low-income students in that state compared to the nation. 23

Every Student Succeeds changes the funding formula on two fronts: first, it gradually reduces the base funding amount, so that by fiscal year 2023, no state state will receive any of the guaranteed base funding it received in 2001. The new law also gradually assigns greater funding weight to states’ low-income populations. By fiscal year 2020, 20 percent of the grant will depend on states’ total student population, while 80 percent will depend on the number of low-income students. 24

With the funding shift, states with more low-income students will receive more funding. The Congressional Research Service estimates that some states, such as Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania, will receive less money under the new formula.

Tennessee, however, is projected to receive more funding. In fiscal year 2015-16, Tennessee’s Title II, Part A funds totaled over $38.8 million – using ESSA’s formula, that share is estimated to increase to over $48.9 million by 2023.25, 26 Projections from the U.S. Department of Education estimate a 3.5 percent increase in Tennessee’s Title II, Part A funds in the first year of ESSA’s new formulas; in fiscal year 2016-17, the state is projected to receive $39.4 million. 27

Competitive Grants

In addition to the formula grants under Part A, Title II also contains several competitive grants for states and school districts. Grant areas include:

- Teacher and School Leader Incentive Fund. States and school districts may use grant funds to explore performance-based compensation systems. Such systems may provide differential or bonus pay to teachers and principals based partly on their students’ performance or improvement. 28

- Literacy Education For All. States may make subgrants to school districts or early childhood education programs. These funds may be used for educator professional development and increasing student literacy in grades K-12. Funding may also be directed to school libraries and early literacy programs. 29

- American History and Civics Education. Institutes of higher education and nonprofit organizations may use these funds to develop Presidential and Congressional Academies. The academies last for two to six weeks and serve American history and civics teachers and students. Money is also provided for teachers and school staff to participate in national civics activities. 30

- Programs of National Significance. Funds are provided for teacher and staff professional development. Funding may also be used to provide leadership training to principals, and to recruit principals to high-need schools. Additionally, states may use grant money to establish a statewide STEM Master Teacher Corps. The Corps is intended to help attract and retain STEM teachers, especially in high-need and rural schools. 31

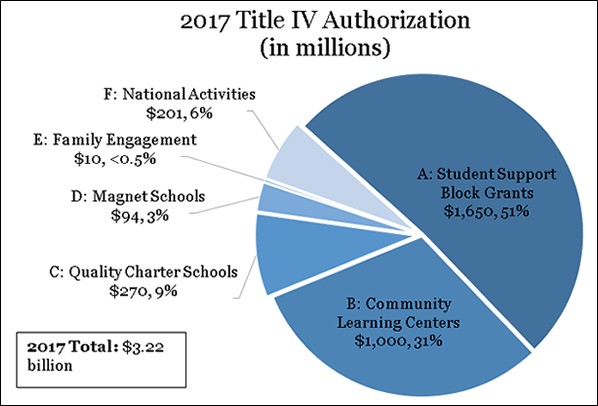

Title IV – Block Grant and Other Programs

No Child Left Behind created multiple programs to improve various areas of education, including school counseling, smaller learning communities, gifted and talented students, physical education, economics education, the arts, domestic violence awareness, and equal education for women. 32 Many of these programs had not been individually funded for several years, however.

Title IV, Part A of Every Student Succeeds consolidates many of these programs into a block grant. 33 These Student Support and Academic Enrichment Grants total $1.65 billion in fiscal year 2017; in 2018 and beyond, the grants total $1.6 billion. 34

Grant funds are intended to provide a well-rounded education, cultivate safe school environments for learning, and encourage the use of technology in education. 35 At minimum, school districts must receive $10,000. 36 Districts that receive over $30,000 must follow several funding requirements:

- at least 20 percent of funds must go toward well-rounded educationby providing access to music programs, the arts, and STEM subjects; offering and paying fees for advanced coursework; and promoting volunteerism and community involvement; 37

- at least 20 percent of funding must be used to support safe and healthy students through drug and violence prevention, mental health services, physical education, and programs to prevent bullying and harassment, among other options, 38 and

- at least some funds must be used for technology. 39

Districts receiving less than $30,000 must commit to only one of these requirements. 40

Additional Title IV Appropriations

In addition to the block grant under Part A, Title IV contains several other sections:

- Part B – 21st Century Community Learning Centers. School districts, community organizations, or other nonprofits may put Part B funds toward creating or expanding community learning centers. Such learning centers provide supplemental services to students when not in school, such as before or after school or during the summer. Learning centers may offer tutoring, counseling, health and wellness services, or other educational programs. 42 In fiscal year 2015-16, Tennessee received almost $21.8 million for community learning centers. 43

- Part C – Expanding Opportunities through Quality Charter Schools. Part C funding may be used for starting new charter schools, or expanding or replicating systems and models that have proven effective. Funds may also help charter schools obtain and improve facilities. Part C funding is used at the national level to evaluate charter schools and their best practices. 44

- Part D – Magnet Schools Assistance. School districts may put Part D funding toward a variety of uses in magnet schools, such as planning or expanding programs and services, buying textbooks and equipment, paying salaries, and professional development. 45, 46

- Part E – Family Engagement in Education Programs. Part E funds may be used to create statewide family engagement centers. These centers encourage parents to support and take part in their children’s education, and may reach out to parents of low-income students, English learners, or other disadvantaged groups. 47

Other Titles

Every Student Succeeds’ remaining funding is authorized under:

- Title III – English Language Acquisition. Title III intends to help English learners become proficient in English and meet the same academic standards as other students and native speakers. 48 School districts receive Title III money through state subgrants, and may use the funds to provide language instruction programs, educator professional development, and services to engage parents and families. 49 In fiscal year 2015-16, Tennessee received just over $5.1 million in Title III funds. 50 Preliminary projections from the U.S. Department of Education place Tennessee’s fiscal year 2016-17 funding for Title III at nearly $5.7 million. 51

- Title V, Part B – Rural Education Initiative. The Rural Education Initiative provides additional subgrants to rural school districts to support school programs. A rural district serves fewer than 600 students, or contains counties with population densities of fewer than 10 people per square mile. 52 Districts may use funding from this part to supplement their other programs under Title I, Part A (Basic Programs for Disadvantaged Students), Title II, Part A (Teacher and Principal Instruction), Title III (English Language Acquisition), and Title IV, Parts A and B (Student Support Block Grants and 21st Century Community Learning Centers). 53 In fiscal year 2015-16, Tennessee received about $4.6 million for rural education. 54 Early estimates of Tennessee’s fiscal year 2016-17 funding show a decrease to about $4.2 million. 55

- Title VI – Indian, Native Hawaiian, and Alaska Native Education. Title VI addresses the unique academic and cultural needs of Indian, Native Hawaiian, and Alaska Native Students. Funding is intended to help students meet state standards; encourage children to study Native languages, history, and traditions; and ensure that teachers and principals have the necessary training and resources to effectively support students. 56

- Title VII – Impact Aid. Impact Aid provides additional funds to school districts impacted by the federal acquisition of land. School districts may include land owned by the federal government that is tax exempt – for example, military bases, Indian reservations, or low-income housing. Title VII money helps districts replace local revenue that cannot be collected through property taxes, so that districts have adequate funding to provide a high-quality education. 57

- Title IX:

- Part A – Homeless Children and Youth. Title IX, Part A, also known as the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, intends to provide homeless students with the same educational opportunities as other students. Funding is awarded to school districts through competitive state subgrants. 58 59 In fiscal year 2015-16, Tennessee received nearly $1.3 million in McKinney-Vento funds. 60 Preliminary estimates for fiscal year 2016-17 put Tennessee’s funding at just over $1.7 million. 61

- Part B – Preschool Development Grants. These grants provide funds for states to build or expand preschool programs and infrastructure. Programs are designed to help low-income or other disadvantaged students transition to kindergarten. Grants encourage partnerships between state and local governments; school districts; preschool providers, such as Head Start; and other community organizations. 62

Transferability

Title V of ESSA increases flexibility with federal funds. States and school districts may now transfer any or all of their federal funding between Title II, Part A (Supporting Teacher and Principal Instruction) and Title IV, Part A (Student Support and Academic Enrichment Block Grants). Additionally, states and school districts may also transfer funds originally intended for Title II-A or Title IV-A to several other ESSA sections:

- Title I, Part A – Improving Basic Programs;

- Title I, Part C – Education of Migratory Children;

- Title I, Part D – Neglected, Delinquent, and At-Risk Children;

- Title III, Part A – English Language Acquisition; and

- Title V, Part B – Rural Education.

States and school districts may not decrease funding to any of the areas listed above by transferring money to other titles, however. Money also cannot be transferred between the above titles – for example, states and districts may not move funds between Title I, Part A and Title I, Part C. 63

Weighted Funding

Up to 50 school districts nationwide may include federal funds in a weighted funding system that directs more money to schools with higher numbers of disadvantaged students. 64

Most school districts consolidate state and local funds at the district level before distributing money to schools. Federal funding, however, is allotted to schools separately from state and local funds, depending on federal guidelines for each program (i.e., Title I, Title II). For convenience, allocations to schools are often expressed in terms of per-pupil expenditures.

Depending on enrollment, demographics, and schools’ needs, districts may set different funding policies – for example, large urban districts may distribute money to schools differently than rural districts.

Under Every Student Succeeds’ weighted funding pilot program, participating districts may combine eligible federal funds with state and local money for the first time. Eligible ESSA funds include Title I, Title II, Title III, Part A of Title IV, and Part B of Title V.

After consolidating all eligible state, local, and federal funds, districts assign “weights” to certain groups of students. Under the pilot program requirements, for example, districts must give schools “substantially more funding” per student for low-income students and English learners. While economically disadvantaged students and English learners are the only groups explicitly mentioned in federal law, the district may choose other subgroups to weight more heavily.

Thus, under a weighted system, funds are distributed to schools based on student demographics, not just attendance – that is, schools with more low-income children and English learners receive more money, even if they have similar enrollment as other schools in the district.

The district must make sure that, when using federal funds, schools continue assisting target student populations. For example, if Title I and Title III funds are consolidated in the weighting funding system, the school must meet the purposes of those titles by serving low-income students, neglected and delinquent children, English learners, and any other applicable groups.

The original weighted funding agreement under ESSA lasts for up to three years. If the results from the nationwide pilot show success, any school district may apply beginning in school year 2019-20, and an unlimited number of districts may participate. 65

Weighted Funding:

Baltimore

In the 2008-09 school year, Baltimore City Schools began using “Fair Student Funding,” a weighted funding system.

Before the budget process begins, schools receive enrollment estimates. All schools receive a base amount for each student: in the 2012-13 school year, the proposed amount was $5,155 per pupil.

In addition to the base amounts, schools receive supplementary money for certain types of students. The 2012-13 proposed amounts were $1,000 for both gifted and struggling students, $641 for special education children, and $750 for students at risk of dropping out of high school.

Not all school funding is included in the weighted system, however. Some districts “lock” certain funds, such as money for custodial services or building maintenance. Schools receive adequate funding for these areas, regardless of their enrollment.

Baltimore City Schools estimates that with the implementation of Fair Student Funding, principals’ control over their schools’ budgets has increased from 3 percent to over 80 percent.

Source:

Baltimore City Schools, Fair Student Funding: What It Means for Your Child, http://www.baltimorecityschools.org/cms/lib/MD01001351/Centricity/domain/6625/pdf/20120316-FSF101-FINAL.pdf (accessed Jan. 18, 2016);

Education Resource Strategies, “Weighted Student Funding,” http://www.slideshare.net/ERSslides/weighted-student-funding-overview (accessed Jan. 18, 2016).

Pay For Success Funding

Several sections of Every Student Succeeds allow states and school districts to use federal funds for “pay for success” programs.

Pay for success funding – also known as a social impact bond – is a way to funnel private money into the public sector. 66 Tennessee currently has limited options for private investment in government. Four entities issue debt:

- The Tennessee State Funding Board issues general obligation bonds authorized by the General Assembly for public projects;

- The Tennessee Housing Development Agency uses bond proceeds to finance low- and moderate-income home loan programs;

- The Tennessee Local Development Authority uses bond proceeds to make loans to local governments and other entities for specific purposes, such as water and sewer recovery facilities or capital projects; and

- The Tennessee State School Bond Authority issues bonds to finance capital projects for public colleges and universities. 67

In addition to purchasing bonds, citizens and organizations may donate private money to the state, with no return on investment. Gifts over $5,000 must be accepted by the Governor, and may be used for a specific purpose. 68 Currently, however, there is usually no way for bond investors to direct their funds to a specific purpose or project. 69

Pay for success programs allow private investors to contribute to a specific public project. Prior to investing money, investors and a public entity, such as a state or school district, agree on a proposed outcome – for example, reducing dropout rates in high school. Then, investors pay up front for the public project in the form of a grant, contract, or other agreement. At the project’s completion, the state or district pays the investors back only if the outcome is achieved. 70 In this way, private investors bear the primary risk of a public project until its completion; if the project is not successful, taxpayer money has not been lost. 71

If the project is successful, however, the state or district may realize long-term savings that cover the cost of repayment. For example, by reducing high school dropout rates, more students may go on to higher education and gainful employment – theoretically, these diverted dropouts will “repay” the cost of pay for success programs by earning higher wages, contributing to the tax base and the economy, and receiving fewer government services.

Throughout the project, the public entity releases yearly progress reports. Additionally, as a condition of the agreement, a third party evaluates the program to determine its success. 72

Under ESSA, states may put Title I, Part D funds toward pay for success programs. 73 Title I, Part D intends to prevent neglected, delinquent, and at-risk children from dropping out of school. States may also provide assistance to dropouts and children returning from correctional institutes to help them continue their education. 74

School districts may also use Title IV, Part A funding for pay for success initiatives. The programs focus on creating safe and healthy schools through drug and violence prevention, mental health services, and encouraging active lifestyles. 75

Currently, states are not restricted from using their own funds for pay for success programs; however, these two sections of ESSA mark the first time states may use federal education money in such programs.

Pay For Success Funding:

New York

While pay for success funding is relatively new in the education world, several states have used it in other areas. In 2013, the state of New York began a pay for success initiative to reduce recidivism and provide work for former inmates. The project planned to reduce recidivism by 8 percent and/or increase employment by 5 percent.

Private sector investors and foundations raised $13.5 million in six weeks for the project – Bank of America investors alone contributed $13.2 million. However, these contributions will only be refunded if the project achieves its goals. If the project exceeds its targets, investors may receive additional returns.

An independent organization, Chesapeake Research Associates, will determine if the goals have been met. The program will last four years, with services provided by the nonprofit organization Center for Employment Opportunities.

If the program meets its objectives, New York estimates it will save $7.8 million in public money from reduced prison costs.

Source:

New York State, “Governor Cuomo Announces New York the First State in the Nation to Launch Pay for Success Project in Initiative to Reduce Recidivism,” December 30, 2013,http://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-announces-new-york-first-state-nation-launch-pay-success-project-initiative(accessed Dec. 22, 2015).

1 Committee For Education Funding, Programs Authorized in S. 1177, The Every Student Succeeds Act, As Approved by the Conference Committee, http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/campaign-k-12/Programs%20Authorized%20in%20the%20Conference%20Agreement%20on%20S%20%201177v2.pdf(accessed Dec. 8, 2016).

2 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 1001, 2015.

3 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 1008(a)(1)(A), 2015.

4 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 1009, 2015.

5 Linda Stachera, ePlan System Administrator, Office of Consolidated Planning and Monitoring, Tennessee Department of Education, e-mail, March 15, 2016.

6 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 1008(a)(1)(B), 2015.

7 Brenda Staggs, Director of ESEA Grants, Office of Local Finance, Tennessee Department of Education, e-mail and attachment, May 25, 2016.

8 National Conference of State Legislatures, Summary of the Every Student Succeeds Act, December 10, 2015, http://www.ncsl.org/documents/capitolforum/2015/onlineresources/summary_12_10.pdf (accessed Dec. 15, 2015).

9 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, USC 20 (2012), § 6303(g).

10 “School Improvement Grants; Final Requirements,” Federal Register 75:208 (Oct. 10, 2010) p. 66363, http://www2.ed.gov/programs/sif/2010-27313.pdf (accessed Dec. 17, 2015).

11 U.S. Department of Education, School Improvement Grants Funding, http://www2.ed.gov/programs/sif/funding.html (accessed Jan. 25, 2016).

12 U.S. Department of Education, School Improvement State Grants, http://www2.ed.gov/programs/sif/sigfy2014allocations.pdf (accessed Jan. 25, 2016).

13 Tennessee Department of Education, School Improvement Grant: Cohort 4, Year 1, https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/education/attachments/sig_awards_cohort_4.pdf (accessed Jan. 25, 2016).

14 State of Tennessee Newsroom, “Tennessee to Receive $10 Million to Invest in Persistently Lowest Achieving Schools,” July 16, 2015, https://tn.gov/education/news/16242 (accessed Feb. 18, 2016).

15 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, USC 20 (2012), § 6303.

16 Offices of Research and Education Accountability, Extended Learning Time, Tennessee Comptroller of theTreasury, February 2014, http://www.comptroller.tn.gov/Repository/RE/ExtendedLearning.pdf (accessed May 31, 2016).

17 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 1003, 2015.

18 Brenda Staggs, Director of ESEA Grants, Office of Local Finance, Tennessee Department of Education, e-mail, March 17, 2016.

19 National Conference of State Legislatures, Summary of the Every Student Succeeds Act, December 10, 2015, http://www.ncsl.org/documents/capitolforum/2015/onlineresources/summary_12_10.pdf (accessed Dec. 15, 2015).

20 Committee For Education Funding, Programs Authorized in S. 1177, The Every Student Succeeds Act, As Approved by the Conference Committee, http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/campaign-k-12/Programs%20Authorized%20in%20the%20Conference%20Agreement%20on%20S%20%201177v2.pdf(accessed Dec. 8, 2016).

21 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 2101(b), 2015.

22 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 2103(b)(3), 2015.

23 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of USC 20 (2012), § 6611(b)(2).

24 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of Public Law 114-95, § 2101(b), 2015.

25 Brenda Staggs, Director of ESEA Grants, Office of Local Finance, Tennessee Department of Education, e-mail and attachment, May 25, 2016.

26 Jeff Kuenzi, Specialist in Education Policy, Congressional Research Service, memorandum, November 17, 2015, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/2644885-ESEA-Title-II-a-State-Grants-Under-Pre.html#document/p1 (accessed Jan. 25, 2016).

27 Brenda Staggs, Director of ESEA Grants, Office of Local Finance, Tennessee Department of Education, e-mail and attachment, May 25, 2016.

28 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 2211 et seq., 2015.

29 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 2221 et seq., 2015.

30 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 2231 et seq., 2015.

31 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 2241 et seq., 2015.

32 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, USC 20 (2012), § 7241 et seq.

33 Alyson Klein, “ESEA Reauthorization: The Every Student Succeeds Act Explained,” Education Week, November 30, 2015, http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/campaign-k-12/2015/11/esea_reauthorization_the_every.html?qs=esea+reauthorization (accessed Dec. 10, 2015).

34 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 4112, 2015.

35 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 4101, 2015.

36 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 4105(a)(2), 2015.

37 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, §§ 4106(e)(2)(C), 4107, 2015.

38 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, §§ 4106(e)(2)(D), 4108, 2015.

39 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, §§ 4106(e)(2)(E), 4109, 2015.

40 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 4106(f), 2015.

41 Brenda Staggs, Director of ESEA Grants, Office of Local Finance, Tennessee Department of Education, e-mail and attachment, May 25, 2016.

42 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, §§ 4201(a)-(b), 2015.

43 Brenda Staggs, Director of ESEA Grants, Office of Local Finance, Tennessee Department of Education, e-mail, March 17, 2016.

44 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 4302, 2015.

45 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 4401 et seq., 2015.

46 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, USC 20 (2012), § 7231f.

47 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 4501 et seq., 2015.

48 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 3102, 2015.

49 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 3115, 2015.

50 Brenda Staggs, Director of ESEA Grants, Office of Local Finance, Tennessee Department of Education, e-mail, March 17, 2016.

51 Brenda Staggs, Director of ESEA Grants, Office of Local Finance, Tennessee Department of Education, e-mail and attachment, May 25, 2016.

52 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, USC 20 (2012), § 7345.

53 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 5003, 2015.

54 Brenda Staggs, Director of ESEA Grants, Office of Local Finance, Tennessee Department of Education, e-mail, March 17, 2016.

55 Brenda Staggs, Director of ESEA Grants, Office of Local Finance, Tennessee Department of Education, e-mail and attachment, May 25, 2016.

56 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 6102, 2015.

57 U.S. Department of Education, About Impact Aid,http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/oese/impactaid/whatisia.htmlhttp://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/oese/impactaid/whatisia.html (accessed Jan. 27, 2016).

58 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 9101 et seq., 2015.

59 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, USC 42 (2012), § 11431.

60 Brenda Staggs, Director of ESEA Grants, Office of Local Finance, Tennessee Department of Education, e-mail, March 17, 2016.

61 Brenda Staggs, Director of ESEA Grants, Office of Local Finance, Tennessee Department of Education, e-mail and attachment, May 25, 2016.

62 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 9212, 2015.

63 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 5102, 2015.

64 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 1501, 2015.

65 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 1501, 2015.

66 The White House, Office of Management and Budget, Paying for Success, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/factsheet/paying-for-success (accessed Dec. 22, 2015).

67 Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury, Quarterly Fiscal Affairs Report, December 2014, http://www.comptroller.tn.gov/repository/ms/20141210Q3FiscalReport.pdf (accessed Mar. 2, 2016).

68 Tennessee Code Annotated, § 12-1-101.

69 Ann Butterworth, Assistant to the Comptroller for Public Finance and Open Records Counsel, Division of Administration, Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury, e-mail, March 14, 2016.

70 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 8002(40), 2015

71 The White House, Office of Management and Budget, Paying for Success, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/factsheet/paying-for-success (accessed Dec. 22, 2015).

72 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 8002(40), 2015.

73 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, §§ 1401(4)(A)(ii), 1401(7), 2015.

74 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, USC 20 (2012), § 6421.

75 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 114-95, § 4108, 2015.