A list of acronyms and terms can be found below the alphabetical entries.

Accretion is essentially the opposite of amortization, and is an accounting process used to adjust the overall amount, or book value, of bonds outstanding on financial statements. Amortization involves writing down the book value of a bond issued at a premium; accretion involves writing up the book value of a bond issued at a discount.

When a bond is issued at a discount — it sells for less than its face value — the issuer will record the bond on its financial statements at par value less the discount. Term bonds with a face value of $100 million, for example, may sell for $95.5 million: $100 million in par value with a $4.5 million discount. The bonds are initially recorded on the financial statements at $95.5 million.

The $4.5 million discount is accreted, or gradually decreased, each year. Because the discount is subtracted from the bonds’ par value, accreting the discount increases the value of the outstanding bonds on the financial statements. When the bonds near maturity, they will be recorded at their par value. For example, the bonds originally reported at $95.5 million will be recorded as $100 million – their face value – immediately before they mature.

See also:

· amortization

· bond discount

· book value

Accrued interest is the amount of interest that has been earned on a security, such as a bond, between interest payments. Most municipal bonds pay interest every six months; in the interim, however, the bond gradually accrues interest until one payment is made at the six-month mark.

When a bond or security is purchased between interest payment dates, the price of the bond includes the accrued interest. The buyer pays the seller the accrued interest as, otherwise, the seller will not receive any of the interest earned while holding the security for a partial period.

For convenience, accrued interest is usually calculated based on a 360-day year, which assumes each month has 30 days.

For example, a 4 percent, $5,000 bond may pay $100 in interest each January 1 and July 1. If a buyer purchases the bond on May 1, four months of interest, or $67, has accrued. In other words, the seller has already earned $67 by holding the bond until May. When the buyer purchases the bond, the money paid to the seller will include the $67 in accrued interest earned by the seller.

The entirety of the $100 interest payment on July 1 will go to the buyer holding the bond as of that date. Thus, by paying the $67 of accrued interest to the seller when purchasing the bond, the buyer effectively earns $37 in interest in that period, or the equivalent of holding the bond for two months from May 1 to July 1.

See also:

· interest

A fee charged in association with administering a loan or other type of debt. The fee compensates the administrative staff for duties such as processing payments, disbursing loan proceeds, and producing financial data or financial statements. The fee that is assessed is indicated in basis points and is calculated based on a percentage of the debt or loan principal outstanding.

Example: The State of Tennessee charges a fee of 8 basis points (or 0.08%) for administering the water and sewer loans for the state revolving loan program.

Bond refundings are typically used to save money by refinancing to take advantage of lower interest rates. Bonds may also be refunded to eliminate certain covenants or obligations imposed on the issuer. In a current refunding, the refunding happens immediately: new bonds are issued within 90 days of the existing bonds being called, and proceeds from the new bonds are used to pay off the old bonds.

In some cases, however, the need for a refunding may occur before the bonds are eligible to be called. In this scenario, there are two outstanding bond issues for the same project. Because the existing bonds cannot yet be called, however, proceeds from the new bonds are not used to immediately pay off the existing bonds. Instead, they are set aside in an escrow account to be used to pay periodic interest on the existing bonds, plus principal when the original bonds eventually reach their call date and are redeemed.

The proceeds from the new bonds in the escrow are usually invested in very low-risk securities, such as State and Local Government Securities (SLGS) offered by the federal government. Although these securities have low yields, they nevertheless earn some income. The timing for receipt and the amount of the investment income is included in the calculation of the amount of refunding bonds that need to be issued to fund the escrow to pay interest and principal on the original bonds. The escrow is structured to have funds timely available to make principal and interest payments on the existing bonds.

In this way, the original, higher-rate debt is functionally replaced with new, lower-rate debt. The issuer now pays interest and principal on the new, lower-rate bonds from the same sources — e.g., taxes — used for debt service on the original bonds. Debt service on the original bonds, however, is paid out of the escrow with money from the new bond proceeds. From the issuer’s point of view, it is no longer responsible for the original bonds, which have been defeased: they are no longer recorded on the financial statements as a liability, and certain bondholder rights may be terminated (looking to the escrow and not the issuer for payment).

From the original bondholders’ points of view, they continue receiving scheduled interest payments on their bonds, with the understanding that the issuer has set in place the process to call the bonds when they reach their call date.

The federal government determined that some issuers abused the advantage of unlimited tax-exempt advance refundings and reduced the number of times an issue could be refunded on a tax-exempt basis. The federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 prohibited further use of tax-exempt advance refundings as of January 1, 2018. Although state and local governments may still advance refund their bonds, the new refunding bonds must now be taxable. As a result, the refunding bonds will likely offer higher interest rates, thereby reducing the money saved on interest payments. Even so, taxable advance refundings may still offer worthwhile savings in some cases.

See also:

· current refunding

· escrow account

· present value (PV) savings

· refunding trust

· verification agent

Local governments with water, wastewater, or gas utility systems are required to file an annual report with the Tennessee Board of Utility Regulation (TBOUR) by the first day of the utility’s fiscal year. This report details contact information for the local government, areas of service, water generation data including water loss calculations, customer counts, what other utilities water is sold to, and training compliance.

An aggregation of AIRs can be found at the following link.

In the context of municipal bonds, amortization is the process of periodically paying off the principal of a bond issue and reducing the amount of debt outstanding. Principal payments may be made to the bondholders themselves or, in the case of term bonds, to a sinking fund that “saves up” in advance for one large principal payment when the bonds mature.

The State of Tennessee structures its amortization schedules, or debt service schedules, for its general obligation bonds with level principal payments. The Tennessee State School Bond Authority (TSSBA) and most local governments use level debt service structures.

Specifically regarding bond premiums, amortization is an accounting process used to decrease the overall amount, or book value, of bonds outstanding on financial statements. When a bond’s coupon rate, or the interest paid to bondholders, is higher than current market rates, the bond will sell at a premium, or for more than its face value. For example, bonds with a face value of $100 million may sell for $104.7 million: $100 million in par value with a $4.7 million premium. The bonds are initially reported on the financial statements at $104.7 million.

Similar to depreciation for capital assets, the $4.7 million premium is amortized each year, or gradually written down. As the premium is amortized, the total book value of the bonds reported on the financial statements decreases. When the bonds approach maturity, they will be recorded at their par value; the bonds originally reported at $104.7 million, for example, will be recorded at $100 million – their face value – immediately before they mature.

See also:

· accretion

· book value

· debt service

· debt service schedule

In the context of municipal bonds, arbitrage involves a state or local government issuing debt at relatively low interest rates due to its federal tax-exempt status, and then investing the proceeds from that debt in the taxable market to earn a higher return.

To help state and local governments save money on interest costs for public projects, the federal government allows the issuance of tax-exempt bonds. Because they keep more of the interest earned rather than paying a portion in taxes, bondholders may be more willing to invest in a municipal bond with a lower yield than a federal or corporate bond with a higher yield. Consequently, state and local governments can typically issue bonds with lower interest rates than their federal or corporate counterparts.

A government might then take the proceeds from the tax-exempt debt and invest them in the higher-yielding taxable market. For example, a local government might issue tax-exempt debt at 3 percent interest, then invest those proceeds in taxable securities yielding 3.5 percent. The government would keep the difference and essentially “make money” off the additional 0.5 percent.

This practice – arbitrage – disadvantages the federal government and reduces its tax revenues. Accordingly, several federal laws restrict or prohibit arbitrage in two main ways:

· Yield restrictions. Generally, governments may not invest bond proceeds above the yield on that bond issue. There are several exceptions; governments may have a short window at the beginning of the project to invest their proceeds without restrictions, for example.

· Arbitrage rebates. If governments do have arbitrage earnings, they must generally send the excess interest to the IRS.

Unlike fixed-rate loans, which typically have the same interest rate over the entire period – e.g., 3.5 percent for 20 years – different maturities of bonds in a single bond issue may have different coupon rates. Maturities toward the beginning of the overall term of the bond issue may have lower interest rates than maturities toward the end of the term. For example, a bond maturing within a year may have a 2 percent coupon, while the bond maturing in 20 years may have a 5 percent coupon.

Therefore, with various maturities paying interest at different rates the average coupon is the average interest rate for the entire amount of bonds that were issued. Average coupon is a calculation that expresses total interest cost as a percentage. Average coupon equals the total amount of interest payments to be made divided by the principal amount of bonds that were issued.

Example: A $20,000,000 bond is issued with 20 annual maturities and a different interest rate for each maturity. The total amount of interest that will be paid over the 20 years is calculated to be $1,750,000. The average coupon equals the total interest cost of the bonds divided into the total principal amount of bonds that were issued, or $1,750,000/$20,000,000 = 0.0875, or 8.75%.

See also:

· bond year

· coupon or coupon rate

A local government’s governing body must authorize the issuance of bonds. This may require the passage of several resolutions. To begin with, an issuer may approve a master resolution, which establishes the general provisions for a type of bond and its issuance. Among other things, the master resolution may set a cap on the total amount of debt an issuer may have outstanding at any given time, or outline the revenues that will be used for debt service.

After the governing body passes the initial resolution, it is published in a local newspaper. With local government general obligation debt, if 10 percent of voters file a petition within 20 days objecting to the bonds, they are subject to a voter referendum. The state does not have a similar process.

The authorizing resolution contains more detail about the structure and repayment of the bonds, any call provisions, and other legal matters.

See also:

· bond referendum

Balloon indebtedness generally refers to a debt structure where all or a substantial portion of the principal matures toward the end toward the end of the repayment scheduleis not repaid until the final maturity. Under Tennessee state law, local government balloon indebtedness is defined as debt with a structure that

· matures 31 or more years from the original date of issuancetakes more than 30 years to mature;

· postpones paying principal or interest for more than three years after the debt is issued;

- capitalizes interest beyond the construction period or three years, whichever is later; or

· has a debt service (principal and interest) repayment schedule that is does not havenot “substantially level” or declining. debt service – principal is concentrated in a few large payments at the end of the term, or matures all at once in a bullet maturity.

Local governments must obtainget approval from the state Comptroller’s Office to issue balloon debt. Some debt issues that meet the above criteria are excluded by state law.

See also:

· term bond

Bank bonds are bonds purchased by a provider of a liquidity facility (usually a bank) in the event of a failed remarketing.

When interest rates rise, for example, bondholders may exercise a put option that requires the state or local government issuer to buy back its bonds, generally at their par value. If the bonds cannot be immediately remarketed to new investors, a bank providing a liquidity facility, such as a standby bond purchase agreement, steps in to purchase the bonds. The bonds are termed bank bonds until they are sold to other investors, or other terms of the standby bond purchase agreement are met. During the time the bonds are held by the bank, the interest rate is usually set at a higher rate.

See also:

· liquidity facility

· standby bond purchase agreement

Bank qualified (BQ) is a designation for a small subset of municipal bonds that provide an economic benefit for commercial banks. Municipal bonds issued by a "qualified small issuer" or an issuer that issues $10 million or less of tax-exempt bonds during a calendar year can be designated as bank qualified.

When commercial banks invest in municipal bonds, provisions in federal law essentially cancel out the benefit of tax-exempt interest. While the bond interest itself is technically tax-exempt, as a result of holding the bonds, banks cannot make deductions they would otherwise take to reduce their overall tax burden. These provisions disincentivize commercial banks from buying municipal bonds, though a commercial bank that invests in bank qualified bonds is able to deduct a portion of the carrying cost of municipal bonds.

To help smaller governments obtain financing for public projects, the federal government created the bank qualified designation. If an issuer does not plan to issue more than $10 million in bonds in a year, it may issue tax-exempt, bank qualified bonds. When commercial banks purchase such bonds, they can take deductions that lower their overall tax burden and make the bonds a more attractive investment.

Commonly used in relation to interest rates and yields, one basis point is 1/100th of 1 percent, or 0.01 percent (or 0.0001). For example, if a bond’s yield has increased from 3.25 percent to 3.50 percent, it has increased by 25 basis points (bps) (or 0.25 percent).

Largely defunct today, bearer bonds are considered property of the “bearer,” or person or entity that holds them. As opposed to registered bonds, no record of ownership or sale is kept for bearer bonds – only a physical bond certificate serves as proof of ownership. To receive interest, physical coupons are detached from the certificate and mailed to the bond issuer or the issuer’s paying agent, and the certificate itself is presented at the maturity date for payment of principal.

Historically, the anonymity of bearer bonds made them a popular vehicle for tax evasion and money laundering. As a result, a 1982 federal law prohibited federally tax-exempt and tax-advantaged bonds from being issued in bearer form.

Issuing bonds is a way to borrow money, often for large projects (e.g., office buildings or parking garages) that are too expensive to pay for with current funds in a single payment. A bond is the borrower’s promise to repay a set amount of money, plus periodic interest, on a specific date.

Unlike a car loan or a house mortgage, a government’s borrowing is structured differently. Instead of establishing a repayment schedule based on a single interest rate and single maturity date, when a government issues bonds, the repayment schedule is based on multiple maturity dates with different interest rates. Thus, at any given time, the government may owe money to thousands of different individuals, businesses, or governments holding its bonds and not just to a single lender.

Both private businesses and government entities issue bonds, and bonds share common characteristics:

· The issuer is the entity borrowing money, such as a state or local government.

· The bond’s par or face value is the amount of money that will be repaid at the bond’s maturity date. Most municipal bonds are issued in multiples of $5,000, requiring a rounding up or down of the amount borrowed.

· The bond’s coupon or coupon rate is the interest rate that will be paid to the bondholder, often every six months. For example, a $5,000 bond with a 5 percent coupon will pay $250 in interest each year, or $125 every six months.

A bond may be bought, sold, and held by many investors over its life before it is paid off. When bonds are originally issued or are traded later on the secondary market, they may not sell for their par amount. A bond’s price depends on how its coupon rate compares to current interest rates on the market for similar investments. If a bond’s coupon rate is lower than the market rate, the bond will be less attractive to investors and will sell for less than its par amount, or at a discount.

In Tennessee, the authority for the state and local governments to issue bonds is found in the Tennessee Constitution and statutes. At the state level, the four primary debt issuers are:

· the State Funding Board, which issues the state’s general obligation debt for capital projects, as authorized by the Tennessee General Assembly.

· the Tennessee Housing Development Agency (THDA), which uses bonds to finance low- and moderate-income home loan programs.

· the Tennessee Local Development Authority (TLDA), which is authorized to issue bonds and notes to make loans to local governments, small businesses, and nonprofits for specific purposes, such as water and sewer recovery facilities.

· the Tennessee State School Bond Authority (TSSBA), which uses bonds to finance capital projects for the state’s colleges and universities.

State law authorizes many local government entities to issue bonds, including counties, cities, metropolitan governments, utility districts, and Industrial Development Boards (IDBs). County and city school districts, however, do not have the legal authority to issue bonds.

See also:

· bearer bond

· Local Government Public Obligations Act of 1986

· long-term debt

· registered bond

· yield curve

A bond anticipation note (BAN) is a type of short-term borrowing used prior to issuing long-term bonds. BANs may be used to generate funding to pay for the construction or acquisition phase of a project. When the project is finished, bonds are issued, and the bond proceeds are used to pay off the bond anticipation notes.

Commercial paper is one example of a bond anticipation note.

See also:

· commercial paper

· note

When an issuer sells a new issue of municipal bonds to an underwriter, the transaction is finalized on the closing date: the issuer and its financing team, along with the underwriter and its legal counsel, sign closing documents. At that point, the underwriter pays for the bonds and the issuer delivers the bonds to the underwriter.

See also:

· delivery date

· delivery versus payment (DVP)

Along with the financial advisor, the bond counsel is an integral part of the issuer’s financing team. The bond counsel looks at legal issues related to a bond issue and subsequently gives a legal opinion. The opinion generally confirms that the issuer is legally authorized to issue the bonds; that the bond issue is a legally binding obligation; and, in the case of tax-exempt bonds, that the bond interest is indeed exempt from specified taxes. The opinion does not address the issuer’s creditworthiness. The bond counsel may also draft or review various documentation, including bond contracts and official statements.

See also:

· rating agency

A bond covenant is a legal provision in the bond contract that sets restrictions on the issuer to protect investors. For example, covenants may require the issuer to:

· raise enough taxes and fees to pay debt service;

· maintain the financed facility at an acceptable level and provide casualty insurance;

· not issue new bonds or debt unless certain thresholds are met – e.g., revenues available for debt service are at least 1.25 times the amount needed for proposed and outstanding debt;

· not take any action that would change the tax status of the bonds from tax-exempt to taxable.

When bonds are issued or sold for less than their par value, the bond discount is the difference between their price and their par value (i.e., face value).

When bonds are originally issued or traded later on the secondary market, they may sell for more or less than their par value. A bond’s price depends on how its coupon rate, or the interest rate it will pay to bondholders, compares to current market interest rates for similar credits.

If a bond’s coupon rate is lower than the current market rate, it will be less attractive to investors, and it will sell for less than its par value, or at a discount. For example, if $100 million of 20-year term bonds pay 3 percent interest while the market rate is 4 percent, the bonds may sell for $86 million: $100 million of par value less a $14 million discount.

The original issue discount is the bond discount when the bond is issued. After the bonds are issued, the issuer records them on its financial statements at their book value: their par value less the original issue discount. As time passes, the discount is accreted, or gradually decreased – as the discount decreases, the bonds’ book value correspondingly increases. Before the bonds mature, they are recorded on the issuer’s financial statements at $100 million, their par value.

See also:

· accretion

· book value

· par value

Bond insurance is a type of credit enhancement where an issuer essentially pays money to increase the credit rating on its bonds. Through a bond insurance policy, an insurance company agrees to pay principal and interest on the insured bonds if the issuer defaults. The issuer’s lower bond rating on the issue prior to insurance is thus upgraded to the insurance company’s higher claims-paying rating (analogous to a bond rating). The premium the issuer pays to the insurance company is offset by the reduced bond interest the issuer pays to bondholders due to the enhanced credit rating.

Because the State of Tennessee has a triple-AAA bond rating — the highest possible rating — bond insurance is not needed to upgrade the ratings on its general obligation bonds.

See also:

· credit enhancement

When bonds are issued or sold for more than their par value, the bond premium is the difference between their price and their par value (i.e., face value).

When bonds are originally issued or traded later on the secondary market, they may sell for more or less than their par value. A bond’s price depends on how its coupon rate – the interest rate it will pay to bondholders – compares to current interest rates on the market.

If a bond’s coupon rate is higher than the current market rate, it will sell for more than its par value, or at a premium. For example, if $100 million of 20-year term bonds pay 5 percent interest while the market rate is 4 percent, the bonds may sell for $114 million: $100 million of par value and a $14 million premium.

The original issue premium is the bond premium when the bond is issued. After the bonds are issued, the issuer records them on its financial statements at their book value, which is their par value plus the original issue premium. As time passes, the premium is amortized, or gradually decreased, and the bonds’ book value correspondingly decreases. Right before the bonds mature, they are recorded on the issuer’s financial statements at $100 million, their par value.

See also:

· amortization

· book value

A bond’s price is the amount of money paid to buy the bond, either when the bond is originally issued or sold later on the secondary market. Depending on how a bond’s coupon rate, or the interest it pays to investors, compares to current market interest rates, the bond’s price may be higher or lower than its par value. For example, if current interest rates are 3 percent, a $5,000 bond with 10 years to maturity and a 2.5 percent coupon may sell for $4,785.

When bonds are issued, the proceeds are the amount of money the issuer receives from the buyers, or underwriters. Depending on how the bonds’ coupon rates compare to current market interest rates, the proceeds may be more or less than the bonds’ par value. In other words, the issuer may receive more or less money when the bonds are originally sold than it will eventually repay in principal.

For example, if $100 million of 20-year term bonds are priced with a 4 percent coupon rate while current market rates are 3 percent, the issuer may receive $115 million in proceeds, or more than the $100 million of par value.

Bond proceeds may be used only for the purposes as provided in the bond contract or authorizing documents.

When an issuer sells a new issue of municipal bonds to an underwriter, the bond purchase agreement (BPA) outlines the final terms of the sale. Among other legal information, the contract outlines information about the bonds, such as maturity dates, interest rates, and call provisions; the purchase price and underwriter’s fees; and any conditions that would allow the underwriter to withdraw from the agreement. The BPA is usually signed and executed on the day of sale.

In general, a bond purchaser is any person or entity that buys a bond. The purchaser may be an underwriter; an institutional investor, such as a fund, bank, or insurance company; or a retail investor, such as a household or individual.

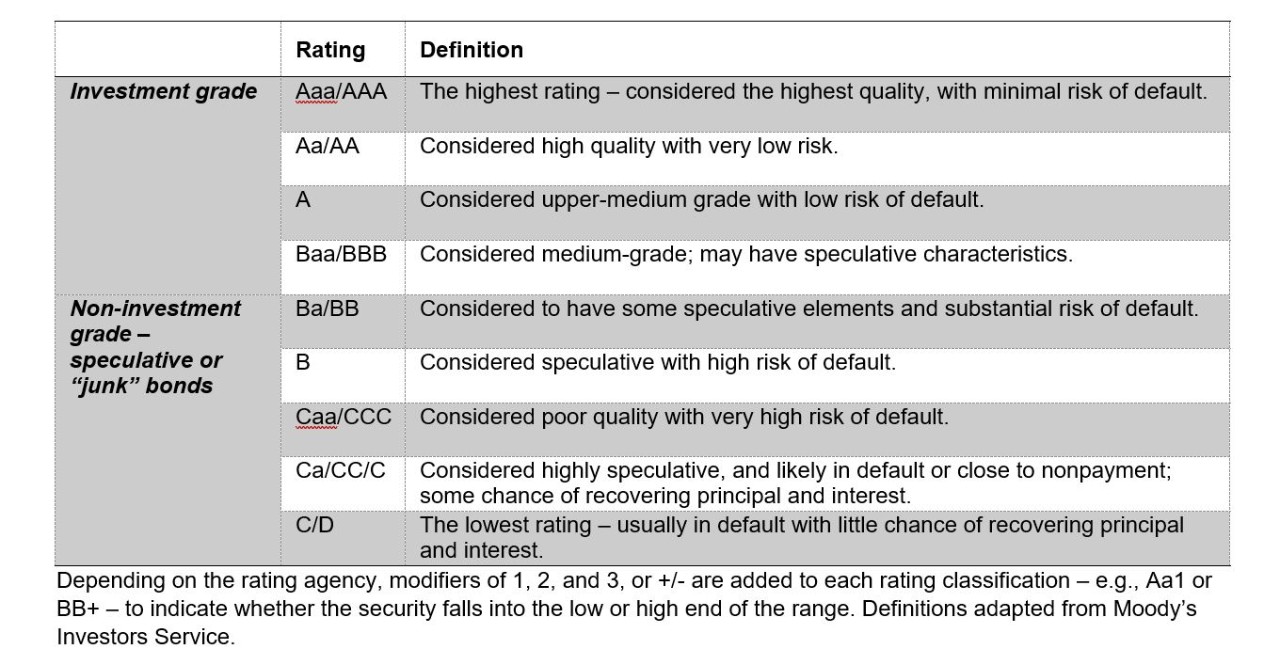

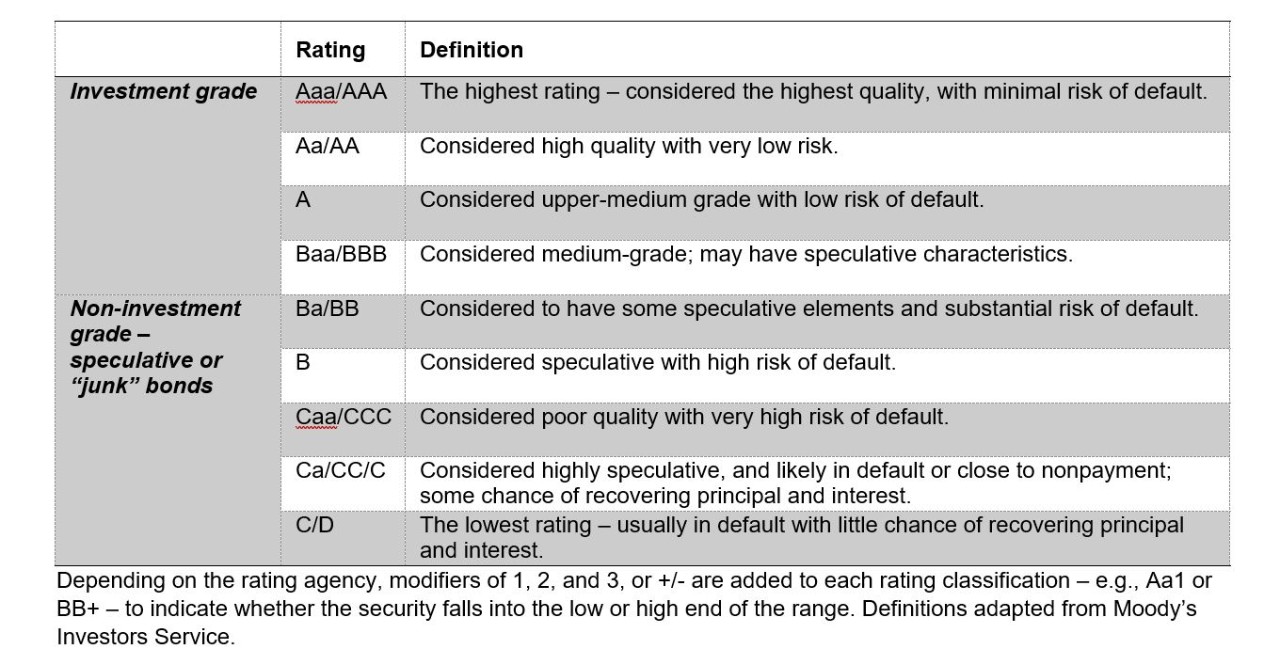

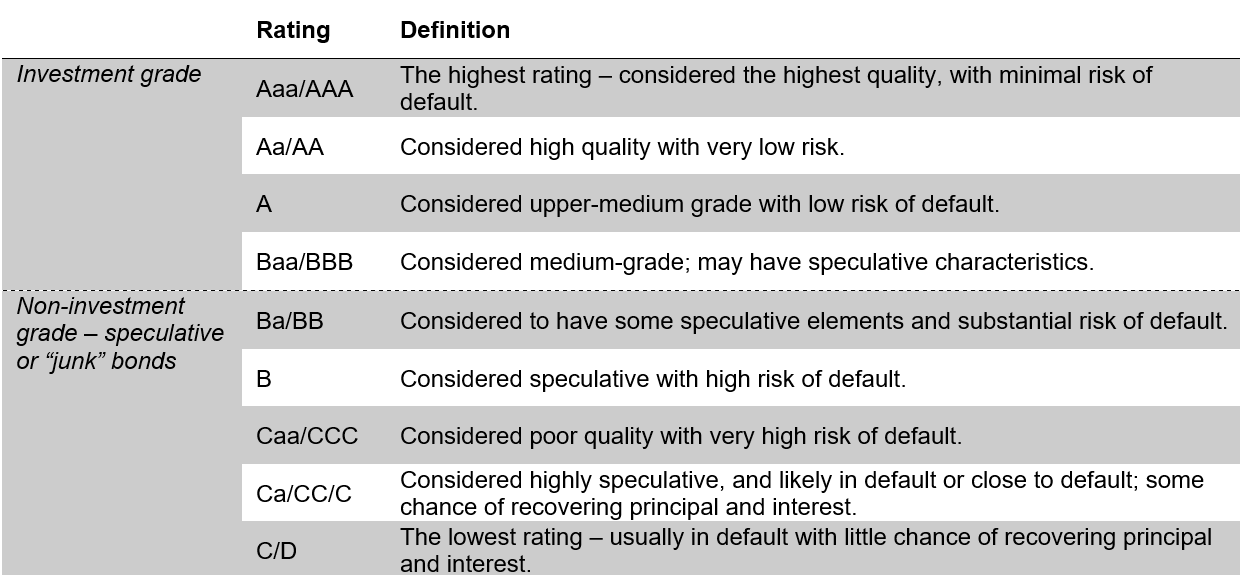

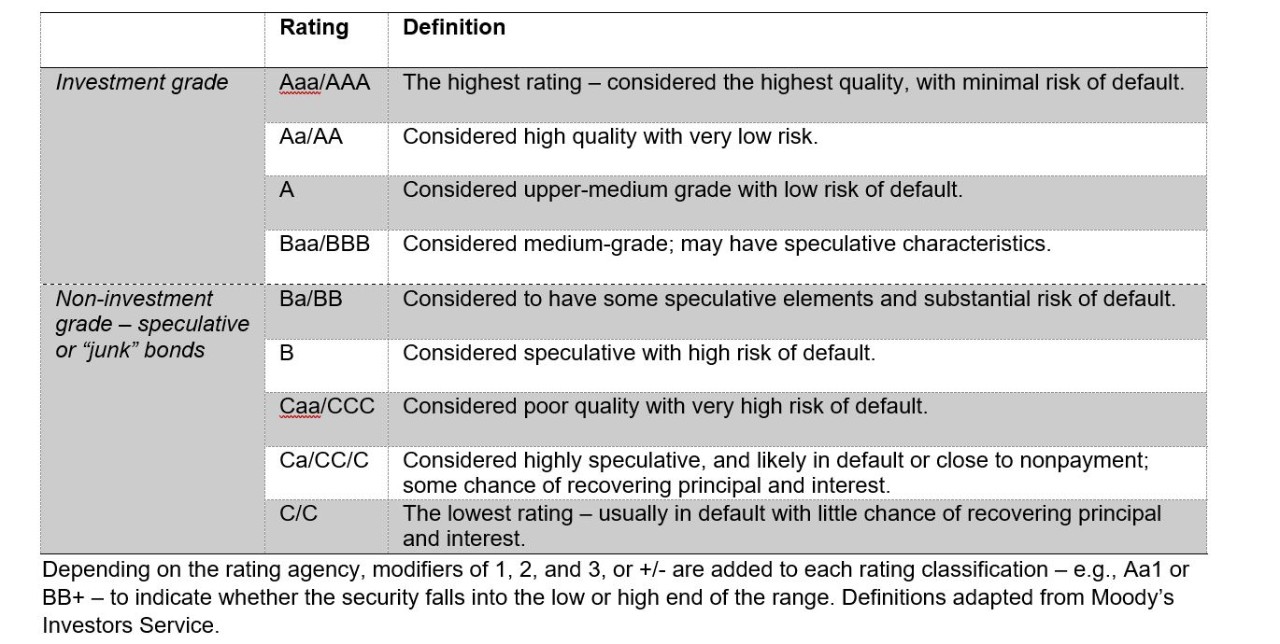

In issuing a bond or credit rating, a rating agency gives its opinion on the bond or other security’s quality and creditworthiness – in other words, how likely the issuer is to make principal and interest payments on time. In determining a rating, the rating agency reviews the issuer’s financial reports, tax structure and related laws, demographic data, and economic statistics, among other things.

Bond ratings are divided into two general categories: investment grade and non-investment grade. Investment grade bonds have been judged relatively likely to pay principal and interest on schedule; non-investment grade bonds, or junk bonds, by contrast, have a higher risk of falling behind schedule or not making payments at all.

The three major rating agencies are Moody’s Investors Service, Standard and Poor’s (S&P), and Fitch Ratings.

If a rating agency judges that an issuer has become less likely or able to make payments on its bonds – revenue shortfalls require an issuer to spend its reserves, for example – the rating agency may downgrade the issuer’s rating one or more levels.

In May 2016, the state’s bond rating was upgraded to “Triple-AAA,” meaning all three major rating agencies considered the state to have the highest credit rating and lowest risk of default.

See also:

· investment grade

· non-investment grade

Through a bond referendum, voters of the entity that is planning to issue bonds vote on whether or not to allow the bonds to be issued.

In Tennessee, state bonds, school bonds issued by counties, and revenue bonds issued by local governments do not need voter approval to be issued. General obligation bonds of cities and counties, however, may be subject to a voter referendum.

As outlined in state law, after local governments adopt an initial resolution to issue general obligation bonds, they must publish notice in a local newspaper. If a petition objecting to the bonds is signed by at least 10 percent of voters and filed within 20 days, the bonds are subject to a referendum. If the vote fails, the bonds cannot be issued at that time, and the local government must wait at least three months before trying again.

Public Chapter 128, Acts of 2021-22 requires a referendum if a capital outlay note is refunded by bonds and the maturity of the refunding bonds exceeds the final maturity of the capital outlay notes being refunded.

The bond trustee, generally a trust company or a trust division of a bank, enforces the bond contract with the issuer. The trustee acts on behalf of the bondholders in a fiduciary capacity, rather than the issuer, ensuring compliance with bond covenants and overseeing operation within approved budgets.

When principal and interest payments are due, the issuer sends the money to the bond trustee. In practice, the trustee may serve in multiple capacities for the issuer, including as the registrar that maintains the list of bondholders and the paying agent that makes payments to investors.

See also:

· trust indenture

A bond year is a figure used to calculate the weighted average maturity of an issue and its net interest cost. Regardless of the bond’s denomination – e.g., whether a bond is issued in multiples of $5,000 – a bond year is a unit of $1,000 of debt that is outstanding for a 12-month period.

To find the number of bond years, the amount of principal maturing in each year is multiplied by the number of years to maturity. The resulting figure – bond year dollars – is then divided by $1,000 to find bond years.

See also:

· average coupon

· net interest cost (NIC)

· weighted average maturity (WAM)

A bond’s yield is its annual return to an investor based on its price, coupon rate, and how long the investor holds it before it matures or is sold. The yield may not match the stated interest rate on the bond.

If a bond’s coupon rate is higher than market interest rates, the bond will trade for more than its par value, or at a premium. For example, if current interest rates are 3 percent, a bond with a $5,000 par value and a 4 percent coupon may sell for $5,430. Although the investor will receive higher interest payments than it would have if it had purchased another bond with a lower coupon, it paid an additional $430 up front to purchase the bond. Thus, the bond’s yield, which takes into account both the bond’s price and coupon, will be lower than the 4 percent coupon rate.

Multiple yields may be calculated for the same bond based on structure and how long the investor holds it:

· Yield to maturity (YTM) assumes the investor will hold the bond until it matures;

· Yield to call (YTC) assumes the issuer will pay off the bond before its maturity date;

· Yield to put (YTP) assumes the investor will force the issuer to repurchase the bond before it matures; and

· Yield to worst (YTW) is the lowest of yield to maturity, yield to call, and any other associated calculation.

See also:

· yield to maturity (YTM)

A book-entry only security is not issued in physical form and does not have a physical bond certificate for each individual bondholder. Instead, ownership records are kept electronically and updated each time the bond is sold. Almost all municipal bonds are in book-entry only form.

See also:

· Depository Trust Company (DTC)

From an issuer’s standpoint, book value is the amount at which outstanding bonds are reported on its financial statements, or “carried on the books.” When the bonds are first issued, book value is the par value of the bonds, plus any premium or less any discount. As time passes, the premium is amortized or the discount is accreted, and the book value of the bonds is accordingly adjusted up or down. More specifically, each time the premium or discount decreases, the bonds’ book value approaches their par value. Immediately before the bonds mature, their book value will equal their par value.

Depending on how the market has changed since the bonds were issued, book value may not correspond to the bonds’ fair market value, or how much the bonds would sell for on the secondary market.

See also:

· accretion

· amortization

· fair market value

Pursuant to Tenn. Code Ann. §§ 7-36-107 and 7-52-601, a municipal energy authority, county, metropolitan government, or incorporated city or town operating an electric plant has the power, with certain limitations, to operate a broadband system, but only after a detailed business plan as described in Tenn. Code Ann. § 7-52-602 has been reviewed by the Comptroller’s Division of Local Government Finance (LGF). The business plan includes a detailed description of the proposed broadband system and pro forma financial data to support the feasibility of the proposed system. Once a complete plan is submitted, LGF has 60 days to review the plan and present the local government with a report on the plan’s feasibility. After that time the governing body may take the actions as described in statute.

Many companies act as both brokers and dealers, and are thus called broker-dealers.

A broker is a person or company that brings together buyers and sellers of securities, such as stocks or bonds. For example, if the broker’s customer wants to buy stock of a particular company, the broker finds a seller, facilitates the trade, and charges a commission on the transaction.

A dealer, by contrast, directly participates in the transaction. For example, a dealer may buy shares of stock from the other party for its own accounts, or sell shares it already owns. While brokers make their money off trade commissions, dealers make money on the difference between the money they pay for the security and the money they sell it for.

An annually adopted document that outlines the expected revenues and expenditures for each fund. Budgets should be structurally balanced, realistic, and contain all debt service payments. All revenue estimates should be meaningfully forecasted. Appropriated budgets are governed by state and local laws and create spending authority limits that are legally binding. Non-appropriated budgets are approved in a manner authorized by state or local laws and not subject to appropriation. The budget is used throughout the fiscal year and amended when necessary.

See also:

- Budget Forecast

- Structurally Balanced Budget.

The

process for estimating budgetary amounts through analysis. A realistic analysis

does not rely on overly optimistic assumptions.

A publication of the Comptroller’s office as adopted by the State Funding Board that helps local governments with budget creation, adoption, implementation, and state oversight. The manual can be found on the Comptroller’s Division of Local Government Finance’s website.

A tool created by the Comptroller’s Office for use by local governments in presenting a summary of their annual budget data by individual fund, including beginning fund balances, revenues, expenditures, and ending fund balances.

Link:

tncot.cc/budget

A call is a provision that allows the issuer to “call” in – redeem or pay off – an outstanding bond ahead of schedule. In doing so, the issuer pays bondholders the par amount of the bond, plus any interest that has been earned in the partial period before the next interest payment. Depending on the bond contract, the issuer may also pay an additional amount to bondholders, or a “call premium” if a call provision is included. If bonds are not subject to call, they are said to have “call protection.”

Bonds are generally called when current interest rates drop below the interest rates on the existing bonds. For example, an issuer may have issued 20-year, 5 percent bonds that may be called after 10 years. If interest rates for a bond maturing in 10 years have dropped to 3 percent at the 10-year call date, the issuer may save money by calling in its existing 5 percent bonds and issuing new 10-year bonds that pay 3 percent interest.

As set in its debt management policy, the State of Tennessee has a preference for issuing long-term general obligation bonds that can be called.

With regard to callable bonds, the call date is the date the bonds may be redeemed and paid off early, as specified by the bond contract. The State of Tennessee’s debt management policy for general obligation bonds allows for call dates to be set no more than 10 years from the date the bonds were issued.

See also:

· call

Capital appreciation bonds (CAB) do not pay periodic interest to bondholders. Like zero-coupon bonds, capital appreciation bonds are sold for substantially less than their par value, then pay out their full value at maturity. For example, a 10-year, $5,000 capital appreciation bond may sell for $3,365. Although the bondholder will not receive periodic interest over the ensuing 10 years, it will receive the full $5,000 when the bond matures.

See also:

· zero-coupon bond

A capital outlay note is a type of short- to intermediate-term financing used by Tennessee local governments after receiving prior written approval by the Comptroller of the Treasury or his designee. Capital outlay notes may be used to finance the construction phase of large projects or to purchase smaller assets, such as vehicles or equipment. Capital outlay notes may remain outstanding for up to 12 years.

See also:

· note

Capital projects involve large-scale projects, such as buying land, building a new facility, or renovating an existing building. Because these large assets last for many years, they may be financed with bonds to spread the cost of the project over its life.

The portion of proceeds from a debt issue that is used to pay interest for a specific period of time. For projects that produce revenue, this is generally the construction period or a period that allows for the project to begin operations and produce revenues to repay principal and interest on the debt.

Governments receive cash from taxes and fees (cash inflows) and spend cash on governmental services (cash outflows). The timing of cash inflows and outflows are not always evenly matched. For example, local governments receive property taxes mainly in the winter months and need additional cash on hand to fund government services (cash outflows) until taxes (cash inflows) are received. The amount of cash on hand needed can vary from one government to the next and should take into consideration unexpected fluctuations in cash inflows and outflows and contingencies. Governments should determine the amount of cash needed to manage its cash flows.

A process of estimating cash receipts, cash disbursements, and available cash during a given period. A cash flow forecast is a tool used by governments to analyze the timing of cash inflows and outflows to ensure cash is available when needed to pay its obligations.

Link: tncot.cc/budget

See also:

- cash flow

- cash management policy

- fund balance policy

A document adopted by the governing body of a government that outlines: 1. The amount of cash to be retained to cover expenditures until revenues are received, 2. The process for determining the amount of cash to retain and when to increase the amount. 3. The position responsible for managing the cash flow process and the minimum level of knowledge, skills, and abilities required.

The policy should address the effect of cash on bond covenants, if applicable and set a schedule for reviewing and amending the policy.

See also:

- cash flow

When a local government plans to issue general obligation bonds or notes to finance certain business parks, a certificate of public purpose and necessity (CPPN) is required. Local governments apply to the Tennessee Department of Economic and Community Development for a CPPN. The application must outline the scope of the project, explain how it will benefit the public, show that the park is less than 10% of the total assessed property value in the local government, and break down costs and proposed repayment.

If the certificate is granted, the local government may then issue general obligation bonds or notes for the project, and thus finance the business park.

Commercial paper (CP) is a type of short-term borrowing where the borrower sells promissory notes that mature from two to 270 days. Although the CP must be paid at maturity, it is often “rolled” — the matured commercial paper is paid off with newly issued commercial paper. In this way, short-term debt may be extended for a longer period of time. Each issue of commercial paper may have a different interest rate.

The State of Tennessee’s current commercial paper program allows the state to borrow up to $350 million, which can be rolled continuously for up to 10 years. CP is used to fund the construction phase of a project; when the project is completed, bonds are issued and the proceeds are used to pay off the commercial paper.

See also:

· bond anticipation note (BAN)

· note

· short-term debt

In a competitive sale, the issuer publishes a notice of sale, which announces its intent to issue new debt. The notice usually includes the date and time of the sale, as well as the specifics of the debt, such as the total amount to be issued, the type, and any parameters for the interest rates.

Bonds are usually awarded to the bid adhering to the requirements of the official notice of sale that will result in the lowest interest cost to the issuer.

The State of Tennessee prefers to use competitive sale for its general obligation bonds.

See also:

· method of sale

· negotiated sale

· private placement

In a conduit financing, the entity issuing the bonds passes the proceeds to another governmental entity or to a nongovernmental entity, such as a private business or charitable organization, usually pursuant to a loan agreement.

Interest on state and local bonds is exempt from federal income taxes, so long as the bonds are used to finance public projects, such as government office buildings or parks. Bonds that primarily benefit private individuals or companies – private activity bonds – are generally taxable, unless they are used for certain purposes outlined in federal law. Among other things, these “qualified private activity bonds” may be used to build low-income housing or facilities for charitable organizations.

Because this subset of private activity bonds is tax-exempt, money may be borrowed by the government at lower interest rates than if the private entity issued its own taxable bonds. Thus, a governmental issuer, the “conduit issuer,” issues the bonds, and typically loans the proceeds to the private entity, or “conduit borrower.” The private entity is responsible for associated principal and interest payments.

See also:

· private activity bond (PAB)

a plan developed by a local government that can be implemented if revenue collections are materially lower than projected due to changing economic conditions or natural disasters. Most plans will contain different levels of cuts depending on the severity of the revenue shortfalls. One of the Seven Keys to a Fiscally Well-Managed Government.

See also:

- Seven Keys to a Fiscally Well-Managed Government

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Rule 15c2-12 provides for continuing disclosure of information regarding municipal bonds. When state and local governments issue bonds, the underwriters must make sure that the issuers have agreed to provide ongoing information to the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB) and investors over the life of the debt.

Examples of such disclosures include:

· financial information and annual financial reports;

· failures to make principal or interest payments on time;

· changes in the bonds’ status from tax-exempt to taxable; and

· changes in credit ratings.

These disclosures are publicly posted on the MSRB’s Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA) website at https://emma.msrb.org. If the information provided is incorrect, or important information is omitted, the issuer may face penalties or fraud charges.

See also:

· Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA)

· event notice

· Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB)

· SEC Rule 15c2-12

Costs that a government issuer pays directly to the service providers in a bond issuance transaction. These service providers include, but are not limited to, the financial or municipal advisor, bond counsel, issuer’s counsel, rating agencies, and bond insurance providers.

Another cost incurred in the bond issuance process is the underwriter’s discount. It is a cost paid indirectly by the issuer to the underwriter for selling the bonds to investors and managing the transaction. The underwriter’s discount is deducted from the proceeds of the bonds at closing.

These costs include, but are not limited to, fees paid to the financial advisor, bond counsel, issuer’s counsel, rating agencies, and any potential underwriter’s discount. The costs are typically expressed as an amount per each $1,000 bond, for example, a $100 fee on a $10,000 debt issuance ($10,000/$1,000 = 10 bonds) would be $100 fee/10 bonds = $10 per bond. The costs per bond amount allows a government to compare fees on various sized bond issues. For example, a $100,000 and a $100,000,000 issuance may have a similar cost per bond.

See also:

- Underwriter’s Discount

- Financial Advisor

- Bond Counsel

A bond’s coupon, or coupon rate, sets the amount of interest the bondholder will receive while holding the bond. Although interest on municipal bonds is typically paid twice a year, the coupon is usually expressed as an annual percentage of the principal amount. For example, a $5,000 bond with a 4 percent coupon will pay $200 in interest each year, or $100 every six months.

For fixed rate bonds, the coupon is set in the bond contract when the bond is issued; it is legally binding and does not change over the term of the bond. As such, it is not affected by subsequent changes in market interest rates – the $5,000 bond with a 4 percent coupon will continue to pay $200 in interest each year, even if interest rates decrease to 3 percent or increase to 5 percent.

A variable interest rate, by contrast, may periodically change or “reset” as it tracks with a specific index (e.g., the London Interbank Offered Rate, or LIBOR).

See also

· bearer bond

In a credit enhancement, an issuer pays a third party to provide a “backup” source of funding for principal and interest payments on its bonds. This added guarantee reduces the risk that payments will not be made to bondholders, and thus allows the issuer to obtain a higher credit rating for its bonds. The new bond rating is based on the credit rating of the entity providing the enhancement, rather than the issuer.

Bond insurance is an example of a credit enhancement: an issuer buys a bond insurance policy from an insurance company, and in return, the insurance company agrees to pay interest and principal on the insured bonds if the issuer defaults. The insurance company’s claims-paying rating — analogous to a bond rating — is used for the bonds.

A letter of credit from a bank is another form of credit enhancement. In this case, a commercial bank makes an irrevocable commitment to pay principal and interest if the issuer cannot make payments. When the bonds are issued, the bank’s credit rating, rather than the issuer’s, is used.

See also:

· bond insurance

· credit facility

A credit facility is an instrument, such as a bond insurance policy or letter of credit, that enhances an issuer’s credit. By using a credit enhancement, an issuer upgrades the rating on its bonds by paying a third party to provide a “backup” funding source for principal and interest payments.

See also:

· credit enhancement

In issuing a bond or credit rating, a rating agency gives its opinion on the bond or other security’s quality and creditworthiness – in other words, how likely the issuer is to make principal and interest payments on time. In determining a rating, the rating agency reviews the issuer’s financial reports, tax structure and related laws, demographic data, and economic statistics, among other things.

Bond ratings are divided into two general categories: investment grade and non-investment grade. Investment grade bonds have been judged relatively likely to pay principal and interest on schedule; non-investment grade bonds, or junk bonds, by contrast, have a higher risk of falling behind schedule or not making payments at all.

The three major rating agencies are Moody’s Investors Service, Standard and Poor’s (S&P), and Fitch Ratings.

If a rating agency judges that an issuer has become less likely or able to make payments on its bonds – revenue shortfalls require an issuer to spend its reserves, for example – the rating agency may downgrade the issuer’s rating one or more levels.

In May 2016, the state’s bond rating was upgraded to “Triple-AAA,” meaning all three major rating agencies considered the state to have the highest credit rating and lowest risk of default.

See also:

· investment grade

· non-investment grade

In a bond refunding, an issuer refinances its debt, often to take advantage of lower interest rates. In a current refunding, new bonds are issued within 90 days of the existing bonds being called, and the new refunding bond proceeds are immediately used to pay off the original refunded bonds. By contrast, in an advance refunding, the call date of the existing bonds is more than 90 days away.

For example, an issuer may have issued 20-year, 6 percent bonds that may be called after 10 years. After 10 years, interest rates for bonds maturing in 10 years may have dropped to 4 percent. The issuer may then issue new bonds maturing in 10 years at 4 percent interest. The issuer calls the existing 6 percent bonds and pays them off with the proceeds from the 4 percent bonds. In doing so, the issuer borrows the same amount of money overall, but saves money on debt service by paying less interest to bondholders.

See also:

· advance refunding

· call

CUSIP number stands for Committee on Uniform Security Identification Procedures number, and is a nine-digit code that uniquely identifies an individual financial instrument (e.g., a stock, a bond, a certificate of deposit).

The first six characters of each CUSIP number are unique for every company or issuer – for example, the first six digits for each issue of the state’s general obligation debt are 880541. The seventh and eight digits denote the type of security – debt or equity – and the ninth digit is a “check” figure based on the previous eight characters.

The date that interest on a newly issued bond or other debt obligation begins to accrue. Also used to identify a particular series for a debt obligation: for example, General Obligation Bonds, Series 2019, dated June 30, 2019.

In general, debt refers to borrowing money and repaying it with interest, sometimes over an extended period of time. Short-term debt is usually repaid within a year, whereas long-term debt may not be fully paid off for 20 years or more.

The Tennessee State Constitution does not allow the state to borrow money for its operating expenses unless it is repaid within the fiscal year. Local governments may issue long-term, so-called “funding bonds” for operating purposes only in extreme circumstances and under strict oversight by the state Comptroller’s Office.

Instead, the state and local governments typically use long-term debt to finance capital projects – large projects, such as office buildings, that will last for many years and may be too expensive to pay for at the time of construction with current funds. By repaying the debt over a longer period of time, the cost of the project is spread over its life.

Bonds, notes, loan agreements, and capital leases are forms of debt.

See also:

· bond

· lease

· long-term debt

· note

· short-term debt

Debt capacity refers to how much debt an entity, such as a state or local government, can support – in other words, how much it can afford to borrow based on its available resources. Various statistics and ratios can be used to measure debt capacity, including debt per capita and the ratio of revenues available for debt service compared to the money actually needed for debt service.

See also:

· debt ratios

Pursuant to Tennessee law, public entities in default on debt must either report the default on the Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA) website of the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB), or for those public entities which are not subject to the requirements of the MSRB, report events of default to the comptroller of the treasury or the comptroller's designee within ten (10) business days of the event. Industrial Development Boards must give notice of default on any debt it has issued (including conduit debt) to the State Funding Board within 15 days of default. The methods of reporting are prescribed by guidelines published by the Tennessee State Funding Board.

For more information see our website.

Debt limit refers to the maximum amount of principal an issuer may issue or have outstanding at any given time. This may be imposed by the State Constitution, statute, charter provision, or policy. For example, under state law, the State of Tennessee cannot issue additional general obligation bonds if the maximum annual debt service on its existing bonds is more than 10 percent of the state tax revenues allocated to the general fund, highway fund, and debt service fund.

There is not a statutory specified debt limit for local governments in Tennessee.

A debt management policy is a guiding document regarding the types and amounts of debt an entity may issue and how that debt is managed. The policy helps to ensure that financial resources are sufficient to fulfill a long-term capital plan. For example, a debt management policy may:

· outline preferences or limitations on the structure of debt – e.g., bond terms no longer than 20 years or level principal payments;

· establish preferences for using competitive sale, negotiated sale, or private placement when bonds are issued;

· set savings thresholds that must be met before refunding bonds; and

· provide guidance on the use of credit enhancements, such as bond insurance and letters of credit.

The Tennessee State Funding Board requires all local government entities that issue debt to adopt a written debt management policy. The Funding Board sets minimum requirements and provides model language for such policies covering transparency, the professionals used in the transaction (e.g., financial advisor, underwriter), and conflicts of interest.

See also:

· Tennessee State Funding Board’s Statement on Debt Management

A publication of the Comptroller’s office as adopted by the State Funding Board that helps local governments with the issuance of debt and with state and federal oversight. The manual can be found on the Comptroller’s Division of Local Government Finance’s website.

Debt ratios are statistics that provide a measure of an issuer’s outstanding debt in relation to various other economic or demographic factors. Rating agencies may use these ratios to determine the credit quality of the issuer or an individual bond issue.

Common ratios include:

· debt per capita: the issuer’s total outstanding debt divided by its population.

· debt service coverage: the ratio of revenues available to pay annual debt service – principal and interest – to the amount actually needed for debt service. For example, if an issuer will pay $15 million annually in debt service and has $20 million to do so, its coverage ratio is 1.33.

· interest coverage: similar to the debt service coverage ratio, the interest coverage ratio considers the ratio of revenues available to pay annual debt service to the amount needed for interest payments.

In Tennessee, any governmental entity that issues debt must complete a Debt Report once the debt is issued. The report must be created and submitted on the online application on the Comptroller’s Division of Local Government Finance’s website and submitted to the governmental entity’s governing body (e.g., the county commission) within 45 days of the issuance of debt , and an additional copy must be filed with the state Comptroller’s Office.

As approved by the Tennessee State Funding Board, the Debt Report includes various information about the debt incurred, such as:

· the type of debt – bond, note, loan, or capital lease – and the purpose of the debt issuance (e.g., general government, education, refunding or refinancing of prior debt);

· the par value of the debt and any discount or premium;

· the interest cost, and whether the interest is taxable or tax-exempt; and

· the method of sale, cost of issuance, and professionals involved on the financing team.

Debt service is the amount of money needed to pay both principal and interest on outstanding obligations.

See also:

· debt service schedule

When bonds are issued, money to make principal and interest payments is typically deposited into and paid out of a debt service fund, restricting or committing the funds for that use. Governments may have several debt service funds, or they may use one fund to account for multiple bond issues.

A debt service reserve fund is a source of “backup” funding used to pay interest and principal if the money otherwise used – e.g., taxes or fees – is not enough to make payments.

Debt service reserves may be particularly important with revenue bonds, where bonds are repaid only with revenues generated by the project being financed. Because these revenues – generally fees or other charges for services – may fluctuate or be unpredictable, investors may be concerned with the issuer’s ability to pay principal and interest on time. As a result, the bond contract may include a debt service reserve requirement that requires issuers to maintain a certain amount of money in a debt service reserve fund (the maximum annual debt service or 10 percent of the bonds’ par value, for example).

Debt service reserves may be funded with bond proceeds; if the issuer needs $100 million for projects and $10 million for its debt service reserve, for example, it may structure its bonds to receive $110 million in proceeds. Debt service reserves may also be funded with any excess revenue generated by the project being financed, or guaranteed with a letter of credit or surety bond purchased from a third party.

A debt service schedule, or amortization schedule, lists all periodic payments of both principal and interest over the life of the bonds.

There are various ways to structure debt service:

· Level principal structures pay equal amounts of principal each year over the life of the debt. As a result, interest payments, and therefore total debt service, decline each time as less interest is accrued off the decreasing principal balance. The State of Tennessee’s general obligation debt is structured with level principal.

· Level debt service structures are similar to many loans with equal installment payments. In a level debt service arrangement, the combined amount of principal and interest payments stay relatively constant each year. Toward the beginning of the term, interest makes up a larger portion of these payments; as principal is paid over the life of the debt, interest makes up a smaller portion of later payments. The Tennessee State School Bond Authority (TSSBA) and most local governments use level debt service structures.

· Ascending debt service may involve deferring principal or interest in early years, or principal payments that gradually increase over time. Ascending debt service may be used when revenues to pay off the debt are expected to grow over time, such as with a new facility or system. Generally referred to as balloon debt and requires the approval of the Comptroller.

See also:

· amortization

. Balloon Indebtedness

· debt service

An issuer defaults when it fails to pay bond interest or principal on time, or does not comply with other provisions in the bond contract.

· In a monetary default, the most serious type of default, the issuer does not pay interest or principal to bondholders on time or in full.

· In a technical or nonpayment default, the issuer continues to make payments on time, but may violate other conditions in the bond agreement. For example, a portion of the project financed with the bonds may be used for private purposes, changing the tax status of the debt from tax-exempt to taxable.

An event of default may occur following a monetary default, or if a technical default is not corrected after a certain period of time. The bondholders may then demand the legal remedies outlined in the bond contract – for example, with a private activity bond default the entire amount of unpaid principal may become due immediately or in a general obligation bond default the government may be required to increase revenues to remedy the delinquent payment and to provide additional coverage for the future.

Defaulted debt of local governments must be reported to the Comptroller’s Office under certain circumstances. This includes conduit debt issued by industrial development boards.

When securities, such as bonds, are sold, the delivery date is the date the transaction is completed and the bonds are “delivered” to the new owner. At that point, the new owner may sell the bonds to another investor.

The delivery date is generally a day or more after the trade date, or the day the buyer and seller agree on the transaction. In the past, when stocks and bonds had physical certificates, the delivery date may have lagged further behind the trade date while the certificate was transferred between brokers.

See also:

· delivery versus payment (DVP)

· Depository Trust Company (DTC)

Delivery versus payment (DVP) is a way of settling transactions when securities, such as bonds, are bought and sold. In DVP, actions on both sides of the transaction are timed to occur at the same time: the buyer’s payment is processed when the seller delivers the securities to the buyer.

This method reduces risk on both sides of the transaction – there is less risk that the buyer will not pay after the securities are received, and less risk that the seller will not deliver the securities after payment is made.

See also:

· delivery date

· Depository Trust Company (DTC)

Depository Trust Company (DTC), a subsidiary of the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC), is one of the largest securities depositories facilitating payment and transfer of securities. Most large banks and broker-dealers are members, and the parent company, Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation, reports processing over 100 million financial transactions a day.

See also:

· delivery date

· delivery versus payment (DVP)

When a local government purchases, constructs, or improves a capital asset it does not expense the total amount in the initial year; instead, the cost is expensed over the estimated useful life. Under the straight-line method of depreciation, the asset cost less any salvage value is divided by years of estimated service life. The purpose of depreciation is to match the expense recognition for an asset to the revenue generated by that asset. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) requires the recognition of depreciation. In Tennessee, local governments must follow GAAP and recognize depreciation expense on capital assets in enterprise funds and the government wide financial statements.

Example: A city’s utility system installs a new water tower that has an estimated life of 25 years at a cost of $250,000 with no estimated salvage value. Instead of expensing the entire $250,000 as an operating expense in the initial year, the city will recognize annual depreciation expense of $10,000 over the next 25 years ($250,000/25 years = $10,000 per year). The utility system’s rate structure will need to be sufficient to cover the annual depreciation expense of $10,000. Since depreciation is a noncash cost, the annual depreciation amount generally can be used for non-income statement items such as: principal payments or capital reserves.

See also:

· amortization

· useful economic life

A direct pay subsidy bond is a type of municipal bond where the issuer receives money from another entity, such as the federal government, to help with interest payments.

Some Build America Bonds (BABs), for example, were direct pay subsidy bonds. Although the bonds were issued by state and local governments, the federal government directly paid issuers 35 percent of the interest they owed to bondholders. That is, the state or local government was only responsible for 65 percent of the interest payment from its own money; thus, for a 6 percent bond, the federal government paid 2.1 percent interest and the issuer paid the remaining 3.9 percent. With the federal subsidy for interest payments, state and local governments could issue bonds at higher, more competitive interest rates.

See also:

· Build America Bonds (BABs)

A discount bond is sold for less than its par value. When a bond is originally issued or traded later on the secondary market, its price depends on how its coupon rate – the interest rate it will pay to bondholders – compares to current market interest rates.

If a bond’s coupon rate is lower than the market rate, it will be less attractive to investors. As a result, it will sell for less than its par value, or at a discount. For example, if a $5,000, 15-year term bond pays 2.5 percent interest while the market rate is 3 percent, it may sell for $4,700.

See also:

· bond discount

A dissemination agent publicly posts ongoing information regarding issuers of municipal bonds, and may be the issuer itself or a third party.

Securities and Exchange (SEC) Rule 15c2-12 requires that certain information about municipal issuers be periodically disclosed over the life of their bonds. Before purchasing bonds from state and local governments, underwriters must make sure that the issuers have agreed to provide ongoing information to the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB).

The dissemination agent submits such information – such as annual financial reports and notices of significant events, such as defaults or rating changes – to the MSRB. The issuer may serve as its own dissemination agent, or may hire a private company to make these disclosures on its behalf.

See also:

· continuing disclosure agreement/undertaking

· SEC Rule 15c2-12

The Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA) system, operated by the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB), is an online source for information regarding municipal bonds. Among other things, EMMA serves as the central repository for official statements and other documentation for new bonds, as well as continuing disclosures (e.g., annual financial reports) related to outstanding debt.

The searchable EMMA website provides free access to members of the public, and is available at https://emma.msrb.org/.

See also:

· Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB)

In general, an escrow is an arrangement where a third party, such as a bank, holds money on behalf of one party. The third party then pays out the money in the escrow account to other parties based on contractual arrangements.

In the context of municipal bonds, escrow accounts are typically used in conjunction with advance refundings. In an advance refunding, interest rates drop before outstanding bonds may be called and paid off early. To “lock in” the lower interest rate and corresponding savings, new bonds are issued at the lower interest rate, and the proceeds are put into an escrow account.

The proceeds from the new bonds in the escrow are then used to pay periodic interest on the existing higher-rate bonds, plus principal when the original bonds eventually reach their call date and are redeemed.

See also:

· advance refunding

· refunding trust

· verification agent

See default.

Event notices – sometimes referred to as material event notices – are the public disclosure of certain events related to municipal bonds that may be relevant to investors. Under the continuing disclosure requirements of Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Rule 15c2-12, underwriters must make sure that issuers of municipal bonds agree to provide ongoing information to the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB), including event notices.

Examples of event notices include:

· delays or failures to make principal and interest payments;

· unscheduled use of debt service reserves or credit enhancements;

· changes in the bonds’ status from tax-exempt to taxable;

· changes in credit rating; and

· bankruptcy or insolvency.

See also:

· continuing disclosure agreement/undertaking

· SEC Rule 15c2-12

See par value.

Fair market value, or market value, is the amount a bond or other security could be sold for in the current market. Depending on market conditions, fair market value may not correspond to the security’s book value, or the value at which the issuer reports the security on its financial statements.

See also:

· book value

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) is a federally owned corporation that guarantees customers’ deposits at member banks. Created in 1933, the FDIC was intended to restore public confidence in banks following the failures and bank runs of the Great Depression.

Currently, the FDIC insures up to $250,000 per depositor on their deposits – e.g., checking or savings accounts, money market accounts, and certificates of deposit. In other words, if an FDIC-insured bank goes bankrupt, customers will not lose their money: the FDIC will reimburse them, dollar for dollar, up to $250,000. The FDIC does not cover stocks, bonds, mutual funds, or other securities.

The FDIC also directly supervises some banks and checks for compliance with several consumer protection laws, such as the Fair Credit Reporting Act and the Truth-In-Lending Act.

The FDIC does not receive taxpayer money, but is primarily funded by membership dues of participating banks.

Under federal law, an investor may or may not have to pay federal income taxes on debt interest. Earnings on corporate bonds and securities from the U.S. Treasury and other federal entities are subject to income taxes. Interest received from certain municipal debt, however, may be exempt from federal taxes.

Municipal bond interest may be exempt from federal income taxes if the bonds are used for governmental purposes, e.g., building a state or local government building. In addition to the federal exemption, state law may exempt interest from municipal bonds from corresponding state and local taxes.

Along with the bond counsel, the financial advisor is a key player in the bond issuance process. The financial advisor looks at current market conditions and offers advice on how to structure, price, and market the new issue, including whether to use competitive or negotiated sale. After the bonds have been sold, the financial advisor may prepare a post-sale report with the final cost of issuing the bonds.

In addition to helping with new issues, the financial advisor may also periodically evaluate whether the issuer could save money by refunding outstanding bonds.

when a local government has either used restricted funds for general government use or is facing financial distress the Comptroller’s Office may require the local government to write, adopt, and follow a financial corrective action plan to correct the problem.

(also called fiscal distress) A condition in which a government has difficulty paying for its current obligations, including debt payments. Numerous and often preventable factors can lead to fiscal distress. A few factors are the following: overestimated revenues due to overly optimistic forecasting, insufficient savings for a financial or other crisis, and overspending. The Comptroller of the Treasury has broad authority to help local governments correct financial distress.

See also:

- Nonrecurring Revenues

- Recurring revenues

A set of ratios that are calculated to help indicate financial distress or improving financial health. Examples are cash as a percentage of expenditures, outstanding debt as a percentage of assessed value, debt per capita, current liabilities as a percentage of available cash.

See also;

- financial distress

- financial distress probability model

A decision tree which uses an entity’s current fiscal year data to classify the probability the entity will fall into fiscal distress in the next fiscal year. The decision tree is built using data science techniques to find financial patterns among distressed entities. An entity is more likely to become distressed if the entity begins exhibiting similar financial patterns to historically distressed entities.

A fiscal year is a 12-month period used for budgeting, accounting, and preparing financial statements. A fiscal year may or may not coincide with the calendar year; in Tennessee, for example, the state and local fiscal year runs from July 1 to June 30, as set in state law. The federal fiscal year begins October 1 and ends September 30.

A fixed interest rate does not change over the life of the security, such as a bond. For example, if a bond’s coupon is fixed at 4 percent, it will pay 4 percent interest semiannually until it matures.

A variable interest rate, by contrast, may periodically change or “reset” as it tracks with a specific index (e.g., the London Interbank Offered Rate, or LIBOR).

See also:

· coupon rate

· interest

· interest rate

An agreement that provides for the purchase of bonds or other obligations of a governmental entity when delivery of such bonds or other obligations will occur on a date greater than 90 days from the date of execution of such agreement.

Full faith and credit is normally used in conjunction with general obligation bonds. Generally, pledging full faith and credit means that the issuer is committed to repaying its bonds from all money it may legally use, and will increase taxes to raise additional funds, if necessary.

See also:

· general obligation (GO) bond

Written guidelines that establish appropriate fund balance levels for different funds, defines conditions warranting the use of fund balance, and how fund balance will be replenished if it falls beneath the government’s established level. The Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) recommends an unrestricted general fund balance level of no less than 2 months of regular operating revenues or expenditures for general-purpose governments, noting that a government’s particular situation may require a higher level.

In Tennessee, funding bonds allow local governments in extreme fiscal distress to issue long-term debt for current operations. Because best practices in fiscal management strongly discourage this practice, funding bonds have rarely been used and are subject to strict oversight by the state Comptroller’s Office.

Although state law allows local governments to issue funding bonds, the Tennessee state constitution forbids the state from issuing debt for operating purposes unless it is repaid within that fiscal year.

As opposed to a revenue bond, which is paid from the revenues generated by the project being financed, a general obligation (GO) bond is guaranteed by the issuing government at large. General obligation bonds are normally backed by the full faith and credit of the government, meaning that the government will use any money available – or raise taxes, if needed – to pay them off. Limited-tax general obligation bonds, however, may limit how much taxes may be raised in this case.

The State of Tennessee’s GO debt, for example, may be paid from any state tax revenues in the general fund, highway fund, and debt service fund that are not legally restricted. In other words, payment of the state’s GO bonds takes priority: unless money in those funds is already set aside in law for a specific purpose, it may be used for debt service, if necessary, rather than other state activities.

See also:

· revenue bond

A governmental bond is a state or local government bond issued to finance governmental purposes, meets the federal eligibility requirements to treat interest on the bond to be excludable from the gross income of the bondholder, and is not a private activity bond.

See also:

· private activity bond